Disclaimer: This blog post was written as an assignment for my AI1 class in collaboration with Daniel Bucher

The essay

In this blog post we want to take a closer look at the following essay: “AI as Normal Technology”, by Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor. The article is really worth a read. The authors uniquely describe their view on how AI shouldn’t be treated as an all-consuming super technology but rather as a normal, evolving and growing technology like the internet. This should, over time, be implemented slowly into our workflows and should be subject to our regulations.

While we agree with their views and also believe that current stances about AI are often based more on hype and a misunderstanding of the underlying technology rather than a true professional prognosis, there is one point that we are missing in the article. “Why should we measure AIs performance in a world that isn’t made for AI?”

Dirt roads and dark factories

We believe a big mistake that often happens with the implementation of new technologies is that we try to implement them in currently existing processes and workflows. This also makes sense from an economic standpoint.

Let’s say you are the company Super Innovative LTD that has a great product and a paying customer base that deeply integrates it in their own processes. Each change in your product can and probably will be met with backlash from your customers. As a business owner you need to make iterative changes to your product and think to yourself for each small change: “Does the added business value outweigh the effort for my customers to change their processes and possibly even train their employees?”. If you don’t do that assessment you risk dissatisfying your customer base and potentially even lose some of your customers. On the other hand, if you aren’t innovative at all you risk being seen as a stale company or provide fewer features than your competition. Also while thinking about your customer value you also need to be in line with regulations given by the state or other regulatory bodies.

This risk-trade-off leads to a system where we have a huge financial incentive to change our products (in our case, software) as little as possible. But why should we believe that the full potential of our new technology in our case LLMs can shine through our old, established ways.

With two examples, “How carriages became cars” and “Dark factories” we want to show how progress requires fundamental transformation.

How carriages became cars

To more deeply understand where we come from in this section of the text we really can recommend the following blog post: Blind to Disruption. Here the author talks about the similarities of the Automobile revolution to the current AI revolution.

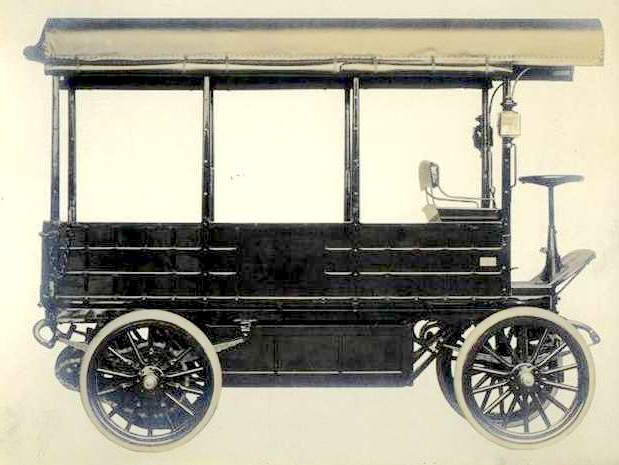

As the first automobiles came to market they were something for the rich and adventurous. But they weren’t really useful. The roads, the existing infrastructure and economy were all made to work within a world of horse travel.

Horses were the most reliable way to transport goods and travel long distances. Automobiles couldn’t function within this infrastructure. Not only were they too expensive for normal people and businesses to purchase, but they also broke down frequently because the rough roads were build for travel by horse (paved roads just didn’t exist yet). Few people even knew how to repair them, and gas was hard to come by. They also weren’t really “cars”, their design looked more like motorized carriages.

But then something happened. Ford invented the moving assembly line, which made these “motorized carriages” cheaper, by making them more accessible, so more people could buy them. As more people bought them the municipalities began paving the roads, engineers invested their effort in improving safety and comfort of car travel, capitalists started selling gas. The car transformed from a motorized carriage that was merely a toy for the rich into something useful for the whole society. The car had such a great impact at that time that we can still see the architectural changes it caused. Look at the old town of a city and then at more modern parts. You will see the impact automobile accessibility had on city planning. (bigger roads, parking spaces, etc.)

The motor got its needed infrastructure and its vessel to express its potential. The companies that realized that they didn’t build carriages but sold mobility, were the only ones that survived this transformation.

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” - a quote often misattributed to Henry Ford.

Dark factories

Again to read more into this topic and as we don’t feel comfortable to talk too much about robotics and factory optimization we can recommend the following two articles: Will the US ever have fully automated ‘dark factories’? and Tomorrow’s Factories Will Need Better Processes, Not Just Better Robots.

Dark factories are highly automated manufacturing plants that are designed to run with no or only little human intervention. They are so automated that they often even run in the dark because no human needs to be there to supervise them. We want to focus on one quote of the tomorrow’s factory article:

When a real factory of the future arrives, it will not look different because we have automated the processes we use today. It will look different because we will have invented entirely new processes and designs for building cars requiring entirely new manufacturing techniques.

Although manufacturing is the oldest industry established after the industrial revolution, there is still a need for constant innovation. This is where entirely new processes, driven by advancements in the field of robotics, sensors, networking and even AI, can show their potential. And again, as it was highlighted in both articles, it isn’t only a problem of the technological advancements, it’s also a risk assessment of economic and organizational viability. We can’t unlock the full potential by simply making the assembly line faster. Our progress needs the right vessel to express itself.

How does it tie back to AI

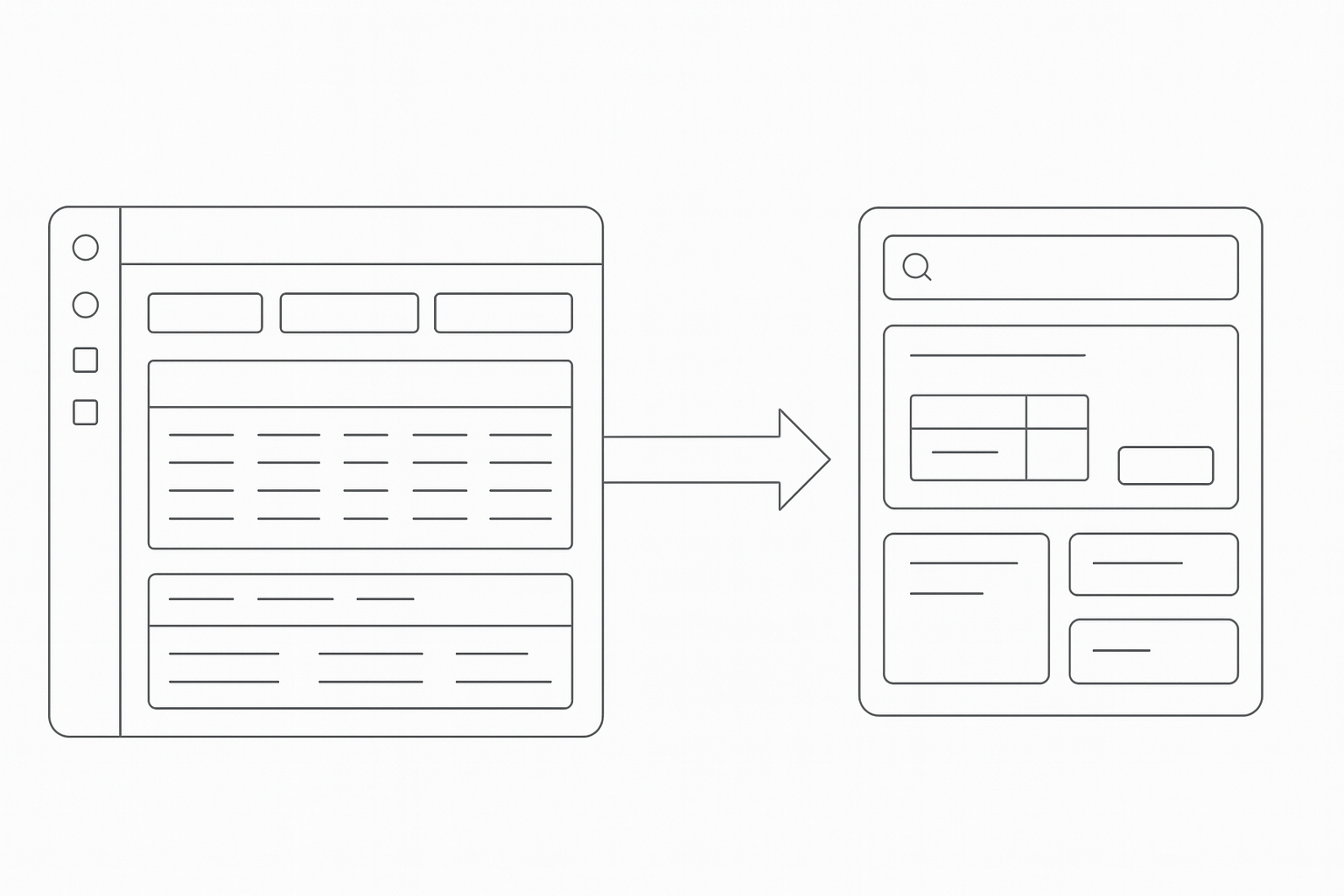

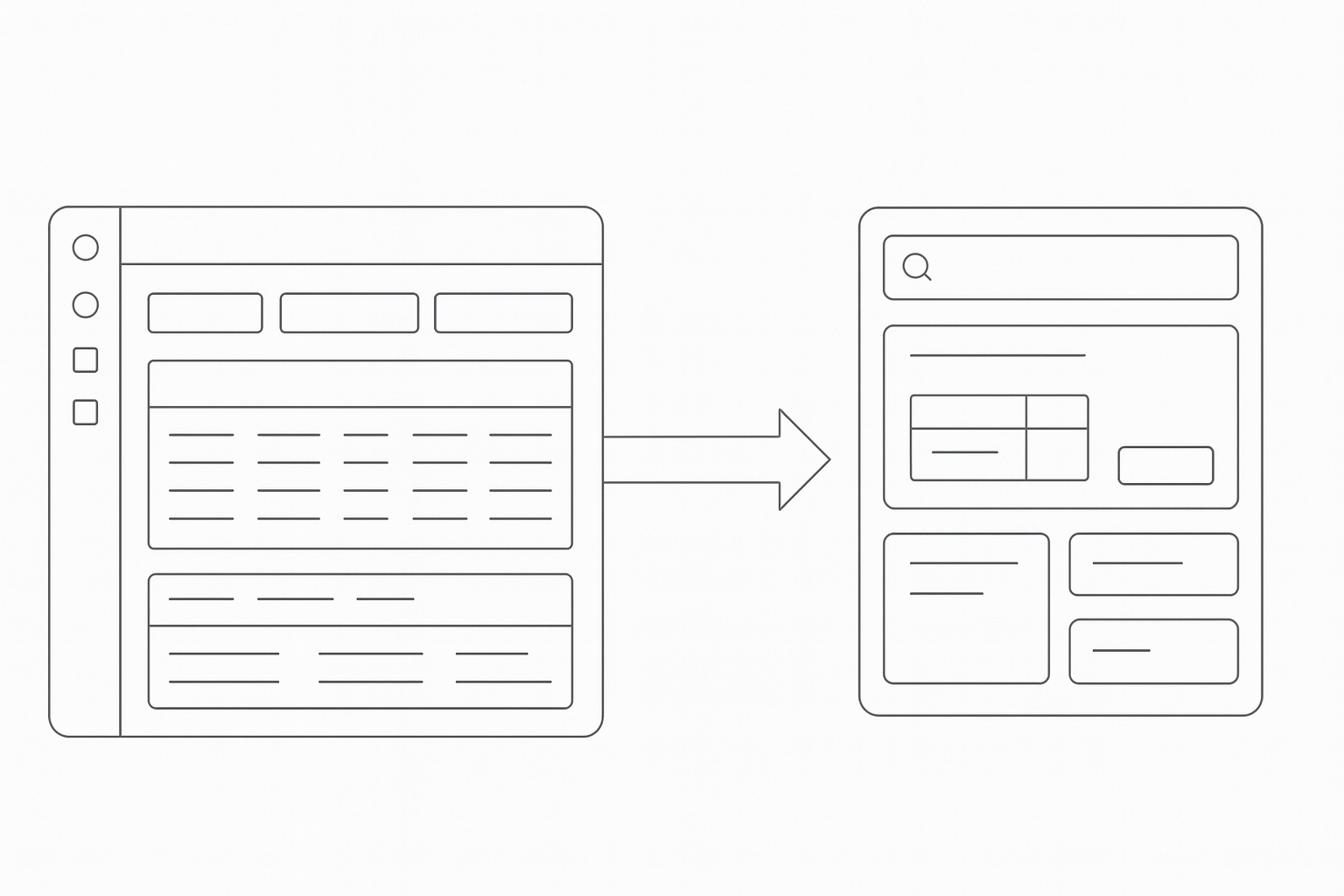

AI seems to be in a similar spot in my opinion. We currently try to supercharge our existing products with AI. We maybe implement a RAG powered chatbot into our knowledge base, add a support chatbot onto our website or maybe even try to use AI in our workflow to automate processes that the AI is suited for and where a clear output can be expected (For example text classification). We are currently motorizing our carriages and supercharging our assembly line. But we aren’t building the car and we aren’t designing the architecture around it. We need to rethink how we build software and tackle the challenges that come with it.

Let’s take an ERP for example. Why should the ERP interface have a graphical interface with buttons if AI can handle function calling and processes underneath and the human only has to tell it what is needed? Let’s say we redesign a User Interface for a car shop ERP into an AI-only-driven software. We would communicate with it only over natural language. We could abstract the confusing data models and the different processes into a helpful chatbot. This chatbot then can read a dataset of 10000 cars or years worth of customer history in seconds and possibly provide you with a more profound answer than you could ever come up with.

We could also change how the program logic works. If we are really creative, rather than defining functions for the AI to use what if it directly works on the database layer and writes SQL statements? Maybe it even manages its own deployment.

We could also change how the program logic works. If we are really creative, rather than defining functions for the AI to use what if it directly works on the database layer and writes SQL statements? Maybe it even manages its own deployment.

As somebody that works in IT only writing about these thoughts makes us feel uncomfortable. But progress is never about comfort, it is about finding new ways. And we believe this philosophy is currently missing in software. An AI centric software approach could be the step where we arrive in “the world of AI”. Surely we also couldn’t let our AI agents have free rein. We would need to set up a control mechanism that still allows for supervision and intervention but doesn’t remove the AIs capabilities.

So how does it tie back to “AI as a normal technology”?

Like mentioned in the beginning of the blog post we mostly agree with the points made in the essay. But as we’ve shown with the dark factory and the carriage to car we need to expand our view on how we design the vessel for AI and the infrastructure surrounding it.

We especially disagreed with the following text snippets from the essay:

“Thus, the speed of diffusion is inherently limited by the speed at which […] organizations and institutions can adapt to technology.”

Yes, because the current incentive to adapt the AI is hindered by the little provided business value. Which can only be achieved by software that allows AI to express its capabilities.

“Diffusion occurs over decades, not years.”

This is true with the method of retrofitting our current software. But if we change our approach, purpose-built AI software would allow for a broader adoption of AI in more use-cases and at much faster speed. In our opinion for this to happen all it would take is a trailblazer that paves the way for others to follow suit.

Do you think you know more than the researchers?

No, we’re fairly certain that Mr. Narayanan and Mr. Kapoor are far smarter and more knowledgeable than us in the area of AI.

But we also believe that often the most knowledgeable people in an area are the most rigid in their way of thinking. They know their domain so well that a new way of looking at AI doesn’t cross their mind easily.

It is impossible for a man to learn what he thinks he already knows.” — Epictetus, Discourses

Conclusion

We wanted to use this blog post to show that, for AI to succeed and not just remain a normal technology that gets adopted slowly, we need a new way to think about AI integration into our existing software suite. Then, we can also start measuring how well AI can really perform.

The next round of revolutionary software will probably move away from our current clickable UIs, with many sub-menus and deterministic software architectures. The product will be much more focused on the business case, and tasks will be described vaguely by the user.

What will that look like? We don’t know, but we will surely be happy to be part of the progress :)